Areas of Islamic Civilization

Book-Culture

At the end of the tenth century, a Baghdadi bibliophile-bookseller called Ibn al-Nadim wrote an annotated and analytical bibliography he named al-Fihrist, in which he recorded the title the thousands of books in ten broad areas produced by the Muslims in four centuries of seemingly incessant activity in compiling books, especially when paper became widely available to them in the eighth century, replacing the more cumbersome and expensive papyrus, parchment, and leather. They include the study of: (1) the Qur’an: its language, readings, exegesis, and “sciences”; (2) Arabic language and grammar, with their various schools; (3) history and its attendant disciplines: genealogy, biography, official state literature; (4) Arabic poetry, pre-Islamic and “modern”; (5) theology, sectarianism, and pious, including Sufi (mystical), literature; (6) Islamic law and its sources, particularly the traditions (Hadith) of the Prophet Muhammad; (7) Philosophy and the ancient sciences: their legacy in classical antiquity, translations into Arabic, and commentaries in its various branches, including the natural sciences, logic, metaphysics, geometry, mathematics, music, astronomy, mechanics, and medicine; (8) popular culture, including storytelling, fables, magic, juggling; (9) the non-Islamic religions of the Near East, like those of the Sabaeans Chaldaeans, and Manichaeans, as well as of farther places: India and China; (10) alchemy and its arts, past and present.

Material Culture

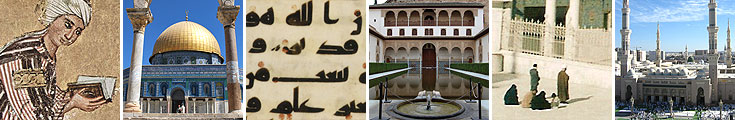

The areas of Islamic civilization left out by Ibn al-Nadim, not unexpectedly, belong to material culture. Not unrelated to book-culture is the area of Arabic calligraphy, manuscript illustration, illumination, miniature painting, and bookbinding; various decorative arts, both religious and secular, on glass, metal, especially silver, brass, and ivory objects; cloth embroidery, especially royal robes; and, above all, architecture. This is the area that reflected the religious and (Arabic) linguistic roots of Islamic civilization, the development of its institutions, and the creativity of its arts when navigating the anti-pictorial sentiment, leading to such arts as the arabesque and geometrical forms. One sees that in royal castles in the Syrian desert in early Islam, in the nucleii of newly-founded cities, in the complex houses with gardens and fountains, in the monumental colleges (madrasas) when higher education became widespread, in the khanqahs, or retreats, of the sufi mystics, in the mausoleums of great men of faith, piety, and politics, and in the monuments that are loud and clear political statements, like the famous Dome of the Rock. Of all architectural objects, the greatest, the most extraordinarily varied, and frequently the most monumental was the mosque (masjid), the prayer place, the representative Islam’s very identity and society’s locus of activities, its minaret for the call to prayer five times a day, its basin and fountain for ablutions in preparation for prayer, and its niche (mihrab) built to identify the direction of Mecca, to which all the Muslims turn their faces in prayer, and where all things Islamic started, including Islamic civilization in the Golden Age of Islam.

Wadad Kadi

Wadad Kadi

Avalon Foundation Distinguished Service Professor of Islamic Studies, Emerita, Department of Near Eastern Languages & Civilizations, University of Chicago

Guiding Questions

1. What is the connection between Islam and other monotheistic religions? List similarities and differences.

2. Describe and define Islamic culture during the Golden Age of Islam, and is it relevant today?

3. What were the defining characteristics and achievements of the Golden Age of Islam? List four major achievements.