The Mesopotamian Origins of the Biblical Flood Story

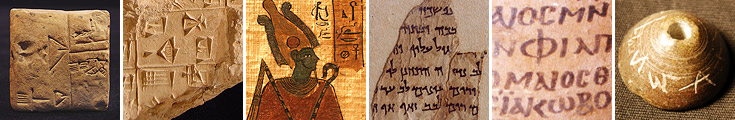

One of the most cherished stories of the Old Testament is the story of Noah, who, on God’s command, built an ark and was spared from the Flood that destroyed mankind (Genesis 5-9). The Biblical account shares many details with earlier Mesopotamian stories, which demonstrates the existence of shared culture traits that spanned the ancient Near East both geographically and temporally, and, moreover, suggests that the Flood story originated in southern Mesopotamia.

In the Mesopotamian myth Atrahasis, written in Akkadian (ca. 1700 BCE), the eponymous Flood hero (Atrahasis literally means ‘Extra-wise’) hails from the ancient Sumerian city of Shuruppak, a city where some of the earliest-known literature has been unearthed. In the myth, the gods send the Flood to solve the problem of overpopulation. However, the god Ea, god of intelligence and helper of man, forewarns Atrahasis of the flood and instructs him to build a boat and ‘save living things’. The deluge lasted for seven days and nights, wiping away humanity. The story is repeated, with some differences, in the Standard Babylonian version of Gilgamesh, which probably dates to the end of the second millennium BCE. In this version, the Flood hero is called Uta-napishti (literally, ‘I (or He) found life’) and the narrative includes a description of the boat coming to rest on a mountain as well as the sending forth of birds to seek out land — both details are included in the biblical account.

Earlier Sumerian sources dating to the beginning of the second millennium support the tradition of a Mesopotamian ‘Noah’. A fragmentary Sumerian myth (the Sumerian Flood Story) follows the account in Atrahasis, adding that the gods settled the Flood hero, here bearing the Sumerian name Ziusudra (literally, ‘Life of distant days’, i.e., long-lived one) in Bahrain (ancient Dilmun) after the deluge; Ziusudra is also mentioned as the sole survivor of the Flood in the Sumerian myth the Death of Gilgamesh. The Sumerian King List, a part-historical part-legendary document that also dates to roughly this time, preserves a tradition in which either Ziusudra or his father, Ubara-Tutu, ruled the city of Shuruppak at the time of the Flood. A wisdom text known as the Instructions of Shuruppak, the earliest versions of which represents one of our oldest pieces of literature (ca. 2600 BCE), contains sage advice from the eponymous king Shuruppak (who in this tradition is the son of Ubar-Tutu) to his son, Ziusudra.

Supporting Links:

“Cuneiform Tablet with the Atrahasis Epic.” The British Museum. Link to resource![]() (accessed May 13, 2010).

(accessed May 13, 2010).

“The Babylonian Story of the Deluge and the Epic of Gilgamesh.” E. A. Wallis Budge. British Museum Department of Egyptian and Assyrian Antiquities, 1920. Link to resource![]() (accessed May 13, 2010).

(accessed May 13, 2010).

Christopher Woods

Christopher Woods

Associate Professor of Sumerology, University of Chicago

Guiding Questions

1. Read the summary of the Atrahasis Epic on the British Museum website (Link to resource![]() ). How do the themes of this story reflect on the belief and value systems of the ancient Sumerians?

). How do the themes of this story reflect on the belief and value systems of the ancient Sumerians?

2. Why do you think versions of flood stories appear in various cultures throughout history?

3. Do you think aspects of real flood events impacted the development of flood stories and, if so, how can we differentiate between factual and mythical elements?

Print Page

Print Page